Out-Of-Pocket Expenditure and Healthcare Revenue

Abstract

This blog post explores the challenges and dynamics of out-of-pocket expenditure in Indian healthcare, where 61.2% of expenses are borne directly by individuals. The government's vision for Universal Health Coverage, replacing the previous "Health for All" goal, emphasizes financial protection alongside accessibility. Contrary to media projections, the private healthcare sector is not solely responsible for high expenditure; government efforts and increasing health expenditure have shown a decreasing trend. The PM-Jay scheme, while beneficial, faces challenges in implementation, necessitating scientific payment methodologies. Regulatory challenges in the private insurance sector and the importance of focusing on outpatient care expenses underscore the need for a balanced approach to reduce financial burdens and achieve sustainable healthcare financing.Introduction:

Out-of-pocket expenditure in healthcare refers to direct payments made by individuals for services not covered by insurance or government programs. In India, where 61.2% of healthcare expenses are out-of-pocket, this places a significant burden, especially for the 12% of the population below the poverty line.

The government's vision for Universal Health Coverage, which aims to provide affordable healthcare to all citizens of India, replaces our previous goal of "Health for All." The current policy debate is about “health for all with financial protection.” This is because every year, 7% of citizens are pushed below the poverty line.

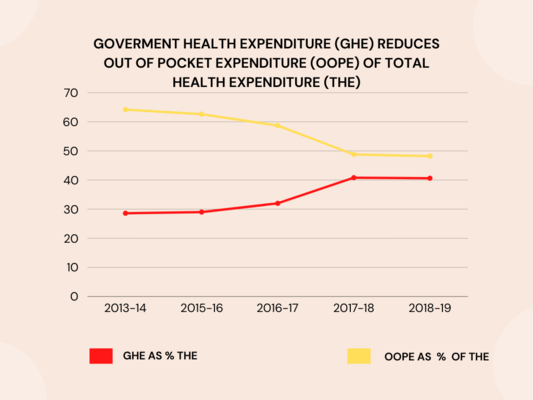

It would be incorrect to blame the private healthcare sector for the high out-of-pocket expenditure in India, as is sadly often projected by the media. It is an established fact that with the increasing government expenditure on health from 1.2% of GDP in 2014 to a projected 2.5% of GDP by 2025 (reaching 2.1% of GDP in 2021), the out-of-pocket expenditure is decreasing. Another aspect often projected in the media is medical inflation, which is highest in Southeast Asia. In reality, hospitals are not solely responsible; the focus should be on the increased premiums of private healthcare insurance.

Government Schemes:

The PM-Jay scheme, covering both the impoverished and non-impoverished, aims to alleviate this burden. However, challenges persist, including unscientific charging methods and delayed payments. In the government scheme, the payments are very low, and hospitals are not supposed to collect money from patients. Many hospitals find it challenging to fit within the scheme's payment brackets, often leading to the rejection of patient treatments. The government seems less cognizant of this issue. Numerous examples exist where hospitals are forced to repay money collected from patients, creating a scar on the government schemes from a hospital's point of view. Unless government scheme payments are scientifically implemented, hospitals will continue to reject patients or become very selective in their choice or will collect money from patients.

Private Insurance Sector and Regulatory Challenges:

Private insurance contributes revenue to hospitals. Recently, IRDA is regulating the pricing of hospital payments. While doing so, IRDA needs to acknowledge that healthcare providers are being underpaid by government schemes, requiring crossside subsidy by allowing higher payments in insurance patients – a reality even in the USA, where Medicare (government scheme) underpayment is cross-subsidized by private insurance.

The higher premium of private insurance is due to the poor penetration of health insurance in India. Furthermore, healthier and younger citizens mostly don't buy insurance; the majority purchasing healthcare insurance are over 45 years of age and may have undisclosed health problems. IRDA should focus on regulating insurence premiums rather than going all the way out healthcare prceing. Healthcare's percentage of profit is in single digits, less than 10%, which could make private healthcare stumble.

OPD Patients and Out-of-Pocket Expenditure:

The most important component of out-of-pocket expenditure is outpatient care (OPD), which is a recurring cost for patients. This part is not covered by government schemes or private insurance. This is the area IRDA needs to focus predominantly on to reduce out-of-pocket expenditure.

To make OPD cashless, digitalization of healthcare is crucial. OPD needs a fast turnaround time for cashless insurance claims. Now that the government has introduced ABDM and upcoming HCX, a positive move in this direction is anticipated. HCX implementation needs to be accelerated by IRDA and insurance companies. This will help reduce expenditure on claim processes at insurance companies. From a healthcare point of view, they need to digitize by moving towards ABDM-compatible software like Nice HMS.

Balancing Act:

Reducing out-of-pocket expenditure involves increasing insurance penetration, achieving 100% cashless reimbursement, and creating networks of commonly empaneled hospitals. IRDA must lead these efforts, ensuring a balanced approach that considers both patient affordability and fair compensation for hospitals.

Conclusion:

As India strives to reduce out-of-pocket expenditure in healthcare, it is vital to address challenges within government schemes, regulate the private insurance sector judiciously, and focus on comprehensive digitization efforts. Collaborative initiatives between regulatory bodies, healthcare providers, and technology platforms are essential for achieving a balanced and sustainable healthcare financing model that benefits both patients and healthcare providers.

This Unlock the Future of Healthcare Management! 🚀🏥🌟

Is managing your hospital, clinic, or lab becoming a daunting task? Experience the ease and efficiency of our cutting-edge Management Software through a personalized demo.